Mr. Watts and the Extortionists

- Jul 3, 2023

- 11 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2023

Originally posted Sept. 21, 2020

When I said that Walter Watts had a relatively good reputation for London theatrical manager of the 1840’s, I probably should have been clearer about the way I was using the term “good.” I’m employing the sort of fine distinction that the character Baldrick from the old “Black Adder” series used to distinguish between a dish of rat and rat sorbet. The rat sorbet could be classified as a dessert because it contained “less rat.” By the same token, a theater manager with a “good” reputation was not scandal-free, but generally had less scandal.

The most infamous and frequently discussed managers of the period by far were Alfred Bunn and David Osbaldiston.

Actor-manager David Osbaldiston, long-time lessee of Covent Garden theatre, was the worst of the lot, with numerous allegations of sexual harassment leveled against him as well as a tendency to promote his own career to the detriment of the rest of the company.

Alfred Bunn was perhaps the most hated and publicly reviled, though. He was seen as a pure profiteer who cared so little about art that once when one of William Macready’s dramas was running long, Bunn had his stage manager drop the curtain on the end of the fourth act, strike the set and move on to the farce without letting the actors deliver the last act of the play. This was the occasion where Macready walked into Bunn’s office and back-handed the manager across the face, incurring a £150 fine for damages and inadvertently setting off what would be the end of the monopoly of the two patent theaters.

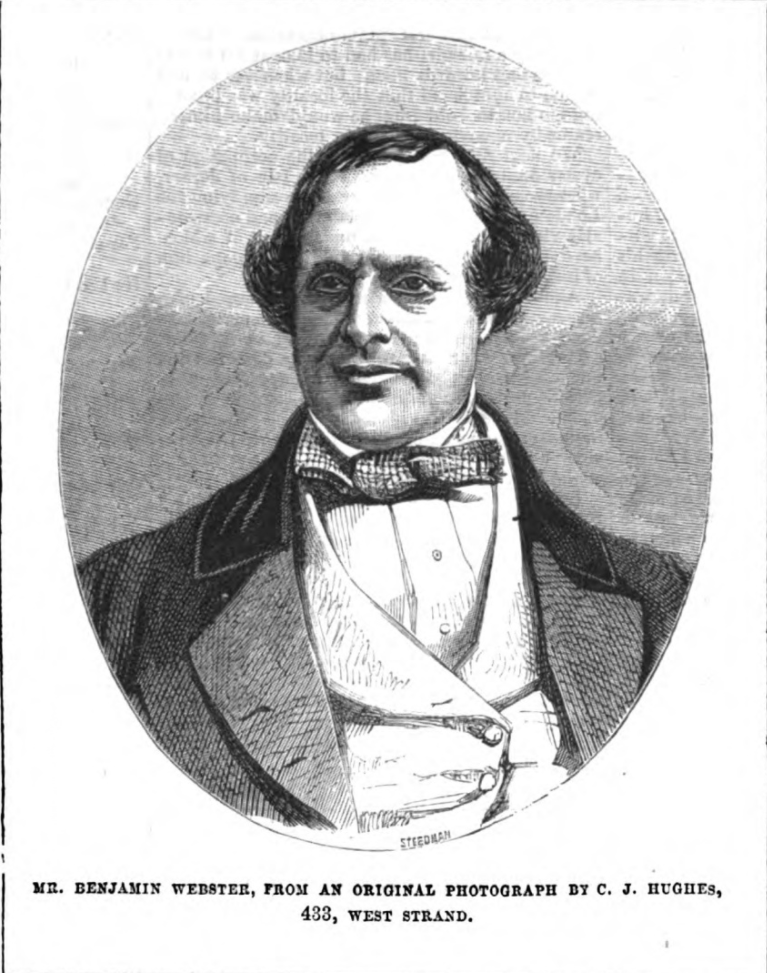

Benjamin Webster, who had the top administrative position at the Haymarket in 1847, was an example of an actor-manager who had a relatively good reputation. His artistic decisions were praised and his treatment of his actors seemed to be even-handed. However, the Theatrical Times registered this complaint about the way he ran his house;

We refer to the system of admitting women of doubtful reputation into the house for the purpose of attracting men thither. The scenes witnessed in the lobbies, and saloon at this establishment are most disgraceful, not only to those who have the directorship of affairs in the front, but also to the police authorities. Why are the impures to desecrate the temples appropriated to pure intellectual art, by an open and shameless traffic in abandoned debauchery, which if it cannot be prevented, should, at all events, not be permitted to insult female modesty? God forbid that we should circumscribe the limits of amusement in which these unhappy creatures live, and move and have their being; or that we should seek to debar them the enjoyment of any pleasure in common with the rest of the world, but we would certainly prevent them from casting a stigma upon the theatre, by making it little better than a syren’s den, a house of wantonness, a portal to the brothel.1

This is not the only mention that I have seen of women who witnesses assumed were sex workers conducting business in the saloons of the Haymarket Theater with at least the tacit permission of the management.

Theatre-lovers were not shy about calling out the failings of mangers. Columns critiquing administrative mismanagement were a regular feature of publications like Actors by Daylight and The Theatrical Times. An article in the latter publication was titled “Managerial Vampires” and began,

There is most assuredly, and certainly never will be, any trade or calling, business, or avocation of what description so ever, in which sheer downright, cold-blooded, heartless, swindling has ever been practiced to so unblushingly great an extent as in that of the theatrical “profession.”2

The break-up of the monopoly on the so-called “legitimate” theatre in 1844 meant that a flood of new managers were attempting to lure patrons and performers once confined to those up-scale playhouses to smaller theaters throughout the city. Actors turned administrators and entrepreneurs like Watts with little previous experience in management attempted to renovate minor theaters to compete for market share against the older, more established venues like Covent Garden, the Adelphi, the Lyceum, and Drury Lane. Their efforts were often clumsy and misguided at one extreme or opportunistic and predatory at another. Both classes of administrative incompetence were bitterly resented by the theatrical establishment. An article titled “How to Live by the Stage” describes an example of a poor specimen of the emerging class theatrical lessee from the summer when Walter Watts was making his managerial debut;

It is a difficult thing to live without money; much can be done with this inestimable panacea for human troubles, and we can buy everything from a politician or a newspaper, to a rope or a pair of stocks, with this same useful convertibility. But if all people had money, there would be no opportunity for enterprise: people would neither take to the road, write melodramas, nor manage theatres.

What is to be done? People must live, and lazy individuals with well-curled mustachios, silver-headed canes, fast paletots, and expensive tastes in general, combined with a decided unwillingness on the part of their ancestors or contemporaries to furnish the viatica, such persons must be awkwardly situated. Railway juggling is past, thimble-rig is local and difficult, and the profit is but small, betting on the races requires some money, and more calculation; cheating tailors is an harmless and useful employment, but may be combined with another profession – in fact, our hero, whoever he may be, is in a dead fix, and so turns manager at once. He recollects some half dozen unfinished, finished – but rejected, accepted – but not acted farces of his own production or a melancholy five-act piece by a rich friend, who loveth the ballet, or a burlesque by a gay young gentleman, who loveth matters of print and paper, and on the strength of some apocryphal former success, or, upon no strength at all, he forthwith takes a theatre, small and quaint in its figure, all corners, like Don Quixote’s Rosinante, and is a gallant, great man at once.

The theatre is taken, half the rent disbursed by the sale of the slip of a room dignified with the epithet of ‘saloon,’ or by privileging of box keepers to swindle the public out of additional shillings or their fractional parts, and then the manager begins to look out for a company.

If the manager possesses a good business as a tailor, a spirited, literary, five-act-unacted friend, his way is clear enough, and he can engage a company costing £50 a night to play in a house holding but £40, he can bring up tragic stars from the country, supported by sticks from the town, he can attempt the legitimate on boards that will not hold it, sport a host of ballet girls who will tumble one against another on the small, cramped stage, although they may individually disport themselves on the table in the green-room for the entertainment of themselves or the lessee Lothario. But if the manager is less fortunately situated, if no ‘victim’ is to be found, away he goes to an Israelite of dangerous liberality, who kindly undertakes the office of money-taker at the box entrance in lieu of the loan of £20 or £30 at the moderate rate of 200 per cent. Thus all the money that comes in is escheated to this Shylock, and the surplus, when there is any, goes to the actors…

Meanwhile, the worthy manager is passing his dubious life of a seedy adventurer, now reveling in the funds out of which the actors are swindled, now borrowing eighteen pence for a dinner at a ‘slap-bang.’ Grumblings in the green-room, occasional speeches to the audience, ‘strikes’ on Saturday evening, ‘sudden indisposition’ on the part of principle performers (there are grades in all theatres!) broken seasons of three weeks; gradual reduction of prices to the lowest ebb of theatrical wretchedness, begin to proclaim the downward progress of the concern. At length the manager is suddenly ‘non inventus,’ the company drop off into private life, Heaven knows where, and the theatre abandoned, a ‘dreary, flat, unprofitable’ wilderness, to the mercy of the next live-by-his-wits individual who may choose to take it.

And this is the use of theatrical property! This is the Drama which is to be the mirror of manners, the imitation, yet model of life, the enjoyment of the educated and wealthy! While London furnishes such systems of living, while theatres are turned into slang cribs and bordellos, while good authors and actors give place to shop boy amateurs: when neat, elegant houses are devoted to entertainments below the worst acknowledged rank, where vulgar inefficiency holds undisputed sway, can the drama be supposed to maintain its position as a civilizing art? Of a truth, such managers had better make a tragic exit at once.3

Although most descriptions of Walter Watts comment on his impeccably groomed mustache and the fashionable cut of his paletots… and yes, I think he even carried a silver-headed cane sometimes… and did write a couple of unproduced farces… and might have had a rich friend (Henry Spicer) who wrote five-act plays … and another (Madison Morton) who wrote burlesques… and a couple more (Oxenford and Lewes) who were playwrights and newspaper drama critics… and he did own at least £1000 of shares in a railroad company… Well, even given all that, it is not at all certain that this piece of invective was directed towards Walter Watts specifically. There were lot of theaters opening in and around London between 1844 and 1850. I included this piece to demonstrate that Watts fell into a type that the jaded theatrical establishment felt they had seen before. At first, Watts appeared to be one of these “shop boy” managers, out only for some short term thrills and hope of cheap profits. When Watts cleared the extremely low bar for acceptable behavior by amateur managers by not immediately driving the Marylebone Theater into bankruptcy and abandoning it, he was largely ignored by the writers of scolding thought pieces and pointed letters to the editor in theatrical publications.

Last week, I told you the story of how in the meeting called after the disastrous opening of “The Belle’s Stratagem,” Watts’ cast and crew rallied around him. Personal knowledge and direct experience from working with him gave Watts more credibility with this group of colleagues than it would later turn out that he fully merited. With the larger London theatrical community, though, once word leaked that Watts had stumbled, they were already primed to believe the worst.

Believing the worst is what brings me to this second story that usually gets left out of recounting of the Watts Scandal, but may have been instrumental in turning public opinion violently against Watts early on in the course of the proceedings against him. On March 27th, five men were arrested for extortion. Mr. Wontner, Watts’ attorney, served as prosecutor for their case. The following article describes their initial hearing:

Sergent Thompson, F11, deposed that on the 12th instant, by previous appointment, he attended at the prosecutor’s house, about nine o’clock at night, and was concealed behind a curtain. Soon afterwards Laidler and Jones came into the shop, and saw Mrs. Lake, the prosecutor’s niece. She asked where the others were, and Laidler replied that they were at a neighbouring public-house. She directed one of them to go for them and Jones left for that purpose. In the meantime, Laidler began talking to Mrs. Lake as though he were a professional man, remarking that Mr. Watts, of the Olympic Theatre, had been arrested for forgery; but he continued, “he have got Clarkson for him, and as £6,000 have been raised on the lease of the theatre, we shall do everything to get him off.”4

This sounds terrible, doesn’t it? This story, carrying versions of the testimony from the police officer that mentioned Watts’ name in connection to the extortionists, was carried in most of the major London papers. In an impressively subtle move, The Era printed an item about this story titled “The Horrors of Extortion” in large type directly above one headed “Mr. Watts and his Defalcations” in small type.5 The paper stopped just short of accusing Watts of somehow being behind the gang of street thugs shaking down local small businessmen. The writer allowed the reader to make that connection on their own.

None of it turned out to actually have anything to do with Walter Watts, though.

Laidler, one of the accused extortionists, was posing as a lawyer (He was actually a waiter.) At his trial in mid-April, he denied the veracity of much of what he said in the conversation with Mary Legg (incorrectly identified as “Mrs. Lake” in the policeman’s report,) niece of Walter Watts’ attorney who was playing a role in a police sting operation designed to break this ring. She would receive an award from the judge of £5 for doing a great public service. There was nothing like £6000 involved in the operation. One of the conspirators ratted out the other four for shaking down a tobacco shop owner for a total of around £100. The only connection to the theatre world was that John Bennet, one of the gang, was revealed to been a former ticket-taker at the Adelphi.

Four of the gang were sentenced to transportation for life. The member who informed on the rest was given two years hard labor. The fact that Watts was not involved with the crime was apparent by early April and his name ceased to be mentioned in newspaper accounts of the case. However, this news story, coming as it did almost simultaneous with Watts’ arrest and seeming to involve his attorney in corrupt dealings, had to amplify negative public impressions of his guilt.

As I said, because it did not pan out to have any connection to Watts, the story of the five extortionists is not even alluded to in any of the versions of the Watts Scandal from writers such as David Moirer Evans, John Hollingshead, or J. Smith Homans who gave us what would become the definitive versions of the story of the affair in the 1860’s. However, because being the shadowy beneficiary of a gang of West End racketeers fit so well with the profile of the low moral standards for the typical “shop boy manager” imagined by individuals in London’s theatrical community like the writer of The Era’s drama reviews (probably E.L. Blanchard), it was a story that had a pejorative impact before it was debunked. In late March, before evidence from the police investigation was made public, journalists appeared ready to make a link to Watts stick. Observers in the theatrical community seemed almost perversely eager to find a junior version of the lecherous venality of a David Osbaldiston or the rapacious, self-aggrandizing, mercenary squalor of second Alfred Bunn in the disgraced manager of the Olympic and the Marylebone. Or perhaps, writers for newspapers were just trying to trying to add some additional spice to what was admittedly a difficult to comprehend story that had too much to do with double-entry accounting.

Extortionists removed, at the center of that story we are left with not an easy to condemn, black-hearted kingpin of a West End crime syndicate, but Walter Watts, dapper, genial, and generous, who loved theatre and spending money, and employed the same impressive levels of ingenuity to running his business as he did in devising schemes to steal money from the large, wealthy corporation who employed him. He enjoyed melodrama, but was not a two-dimensional cliché from the well-worn sagas of that genre.

The link between him and the case of the five extortionists was so tenuous that had it occurred at any other time, it probably would not have been newsworthy. Happening almost simultaneous to his arrest though, I believe it helped strengthen prevailing negative impressions in the London theatrical community and in the press. The story intensified rumors of scandalous and additional undisclosed criminal behavior on his part. Bearing in mind how close Watts came to beating the charges against him, this prejudicial incident may have, in the end, had a literally fatal impact.

“Modern Managers No. 2. Mr. Benjamin Webster.” The Theatrical Times, No. 56. Saturday, May 29, 1847. Page 163.

“Managerial Vampires.” The Theatrical Times, No. 87. Saturday, January 1, 1847. Page 2.

Oxoniensis. “How to Live by the Stage.” The Theatrical Times, No. 122. Saturday, August 18, 1848. Page 82-83.

“Bow-Street – (This Day.)” The Sun: London. March 27, 1859. Page 3, col. 1.

“The Horrors of Extortion.” The Era: London. March 17, 1850. Page 9, col. 2.

Comments