Anna Cora Mowatt, Polkamania, and “The Serious Family” - Part I

- Oct 9, 2023

- 12 min read

PART ONE - SERIOUSLY CLASSIC

The spring of 1852 was one of the saddest, most challenging times of Anna Cora Mowatt’s life. Her husband, James Mowatt, had just died. As a result of her association with Walter Watts, the manager of the Marylebone and Olympic Theaters, who was arrested for embezzling millions from the Globe Insurance Company, her career was now in shambles and her life savings were decimated. Teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, she had been forced back to work, unable to be with her dying spouse in his final hours. Mowatt, too, had been desperately ill for many months. She suffered with what contemporaries called a “brain fever.” In part, I believe this malady was what we laymen used to call a "nervous breakdown."

In the midst of all this tragedy and turmoil, when she was under the deepest cloud of scandal and public disfavor of her entire career, Mowatt unexpectedly made one of her more joyously transgressive choices of roles. She added a new play to her repertoire -- Morris Barnett’s popular comedy, “The Serious Family.” Instead of playing it safe and selecting the character of Mrs. Torrens, the virtuous wife, Mowatt went with the more daring option and selected for herself the role of the flirtatious, convention-defying widow, Mrs. Ormsby-Delmaine. This was definitely the more fun alternative. However, it was quite a risky option for a recently widowed actress who was still under the shadow of a major scandal.

[A full cast recording of "The Serious Family" is available at Librivox ]

There are many elements to this play itself that are a little surprising. Regular readers of this blog will probably be relieved to find that they will not be burdened with a fresh dose of my opinions on melodrama this week. “The Serious Family” moves us to a dramatic genre I have yet to mention in any of these essays. This play is perfect example of a drawing room comedy --- quite literally. Each scene takes place in a drawing room. You may be forgiven for associating drawing room comedies with the 1890s or the 1920s. Most classic examples of this genre date from those decades. However, “The Serious Family” and the hit dance tune it spawned were very much creations of the late 1840s and the fad called “Polkamania” that swept the U.S. and the U.K. at that time.

The Playwright

Recently I moved the blog to a new website. In the process I ended up rereading my past essays. I became painfully aware of how often I tend to reuse certain phrases. One set of words I noticed turning up many times occurred when I quoted the London newspaper, the Era’s, drama reviewer. When attributing a specific source, I almost invariably say, “Probably E.L. Blanchard.” Morris Barnett is the one of the reasons that pesky “probably” must be present.

Like Blanchard, Barnett became part of The Era’s pool of “penny-a-liner” drama critics. Like Blanchard, Barnett was also a playwright. He had the requisite experience to have composed any of the reviews that offer the very confidently insightful structural critiques of the texts that I tend to assign to Blanchard.

In addition to writing, Barnett was also a successful actor. His family was both French and Jewish. Barnett spent his early years in Paris. His initial profession pursuits were in the field of music. Barnett experienced his first success on the English stage as a comedian in theaters in the resort towns of Brighton and Bath. Impresario Alfred Bunn brought him to London to perform at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1833. Barnett made his first hit in the role of Tom Drops in Douglas Jerrold’s “The Schoolfellows.”

In 1837, he wrote and starred in “Monsieur Jacques” (sometimes identified as "Pauvre Jacques" or "Poor Jacques") at London’s St. James Theater. Barnett’s was not the only production with Gallic theme to achieve success at this venue. The Comédie-Française made frequent visits to the St. James. Contemporaries identified “Monsieur Jacques” as a burletta, or a type of short comic opera. Today, we would probably be content to label the show as a musical comedy. Barnett toured with the play through the early 1840s. In 1849, his younger brother, Benjamin staged a successful revival of “Monsieur Jacques” at the Olympic. Morris Barnett took up the role again in 1854 for another revival that toured the U.S.

The Play

Barnett’s facility with the French language served him well as a playwright. Not only did he draw on Gallic cultural archetypes as he did in “Monsieur Jacques” to create original material, but several of his plays are translations and adaptations of French comedies. “The Serious Family” takes its inspiration from “Le Mari à la Campagne” (“The Husband in the Countryside”) by Jean-Francois Bayard.

As soon as I give you the subtitle of original work, a structure supporting characters, situations, and themes in Barnett’s comedy will become immediately transparent. The full title of Bayard’s play is “Le Mari à la Campagne, ou Le Tartuffe Moderne” (“The Husband in the Countryside, or The Modern Tartuffe.) The original comedy upon which Barnett based “The Serious Family” is a version of Moliere’s classic 1664 satire on the intersection of religious hypocrisy and ruthless social climbing updated to France in the 1840s. Although banned during its initial run, “Tartuffe” would become the most frequently performed play of the Comédie-Française. Bayard’s updated version of Moliere’s classic was also selected by that company for performance.

(If you need a refresher on that theatre classic – or just a good excuse to watch an excellent production of “Tartuffe”– let me recommend this recording of version from 1983 by the Royal Shakespeare Company )

In Moliere’s comedy, the father, Orgon, holds such absolute sway as head of the family, that even though all his relatives know that he is Tartuffe’s dupe and is making disastrous decisions to the determent of them all, they have no powerless to stop him. Bayard and Barnett’s comedies tell the stories of fathers struggling to metamorphose from helpless and unhappy puppets to regain their rightful role as heads of their households.

In the Victorian era versions, it is the character of the mother-in-law – a mere comic harpy in Moliere’s original – who rules the family with an iron fist. The Tartuffe-like character in both these versions is merely a minion who aids in enforcing her will and functions as a yes-man who bolsters her already-established prejudices. Although he is onstage from the first moment of the play, this character has little real power of his own. Other characters openly mock and defy him without suffering real consequences. The Tartuffe-like character in Bayard and Barnett’s versions is more of an annoying obstacle than a real threat to the protagonists.

Unlike Moliere’s philosophically minded and even-tempered Cléante, Bayard and Barnett’s raisonneur characters originate from completely outside the family circle. Both are old friends of the father character who recall an wild youth at odds with the pious façade he has now assumed to please his demanding puritanical in-laws. Breaking with a tradition that typically portrayed raisonneurs as wise but ineffectual characters, Bayard’s César Poligny and Barnett’s Captain Murphy Maguire are men of action. Poligny and Maguire are both naval officers. Instead of merely offering advice and pleading the case of reason as Cléante does, Poligny and Maguire formulate a plan of attack against the antagonists, organize the family to work as a unit, and execute an effective counteroffensive.

Poligny and Maguire are also not purely men of reason. Unlike Cléante, each of them has his own romantic subplot. (In fact, I would say that Captain Maguire’s subplot is probably more entertaining than the main plot involving the father and his wife.) Although each man eloquently argues for reason, their actions demonstrate that are both men of passion who themselves are swayed by sentiment and romance.

Romance is perhaps the essential quality that differentiates the two Victorian-era revisions from Moliere’s original. The French master-playwright’s satire ended with a peculiarly powerful deus ex-machina. No less puissant a figure than King Louis XIV was required to make a surprise entrance into the plotline and extricate Orgon and his family from the clutches of Tartuffe. In Bayard and Barnett’s comedies, their focus is not on exposing the lecherous corruption behind a religious façade. Their Tartuffe-like characters don’t ever rise to the level of posing an existential threat to the families. Instead the biggest threat to the families in each of these comedies is that the fathers are putting on an outwardly pious front to please their mother-in-law while taking “trips to the country” to secretly lead a life of dissolution that is causing them to become increasingly emotionally detached from family life. The problem is solved in each play via the magic of love.

In “Le Mari a la Campagne” and “The Serious Family,” the tangled elements of the plot begin to miraculously unravel when the father – much to his initial surprise – discovers that the woman with whom he is madly in love is actually his very kind and unusually forgiving wife. Reconciling with her allows him to finally take his proper place as head of the family and put his disordered house in order.

In Barnett’s version, the pathway for the magic of love is smoothed by the magic of music. Barnett, a talented musician himself, was well aware of the power of music. His version of this show included two songs and concluded with a big ensemble dance number that helped the audience get swept up in a general feeling of happiness and forget about some thin spots in the comedy’s plot. “The Serious Family Polka” became a hit that was included in several compilations of popular dance tunes of the day.

Bayard and Barnett’s modern “Tartuffes” are sentimental romantic comedies that wink a forgiving eye at religious duplicity rather than pointing an accusing finger. The person who gets caught red-handed in a highly scandalous situation and continues to lie for a few moments about his piety and virtue even in the face of obvious evidence of his own perfidy is not led away by the authorities to an uncertain but undoubtedly awful fate. Instead these characters are lovingly forgiven and placed in a position of responsibility supervising the welfare of everyone around them.

As you can see, although perfectly good romantic comedies, Bayard and Barnett’s versions lack a great deal of the bite and impact of Moliere’s original. Though very successful with audiences in their day, neither Victorian era revision went on to become a classic in its own right to rival the iconic comedy upon which they were based.

Critical Reaction

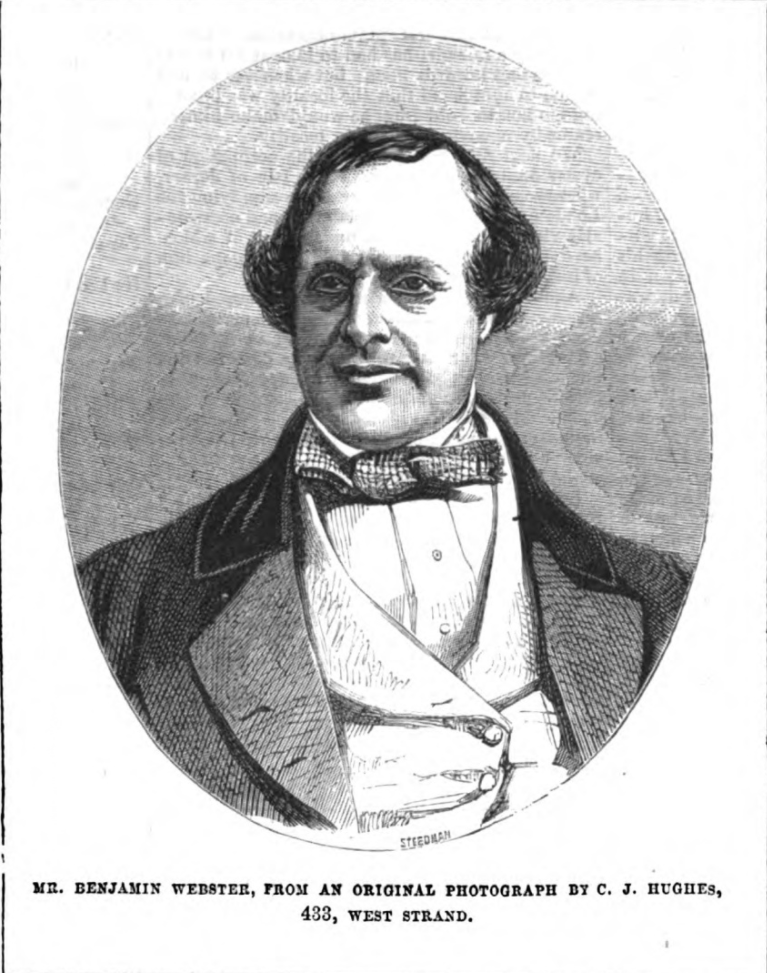

Barnett was extremely fortunate in the venue that selected his play for its premiere. The Haymarket was at this time in the very top tier of London’s theaters. Respected actor-playwright Benjamin Webster was at the helm as manager and lined up an all-star ensemble for the show. “The Serious Family” featured such favorites as James Buckstone, Fanny Fitzwilliams, and James Wallack. Webster had such confidence in the script that he cast himself in the role of the father, Charles Torrens. Any actor undertaking this part assumes the delicate task of not only carrying one of the show’s romantic leads but maintaining the audience’s sympathy while switching between the character’s pious veneer and the first act and his more feckless identity as a Belgrave-Square rake in the second.

The 1849 production of “The Serious Family” at the Haymarket also had the advantage of what in television programming would be called a “strong lead in.” William Macready was starring in a number of lavish Shakespearian productions. These shows were in preparation for his upcoming tour of the U.S. This visit would turn out to be the most memorable series of performances of his career for reasons that no one could have foreseen at that moment (See the Astor Place Riot ). Even without that prescience, all of London was turning out to see the great tragedian’s sumptuous stagings of familiar favorites from the Bard. Barnett’s sparkling comedy was a pleasing palette cleanser between heavy helpings of Macready’s Hamlet and Macbeth.

There were reviews of “The Serious Family” in all London’s major papers that regularly carried theatrical critiques. Word from these writers was consistently laudatory. The following is typical:

Morris Barnett has achieved a most brilliant success. His new comedy, entitled The Serious Family, which was produced here last evening, is one of the most amusing, one of the best built, one of the best written, and far and away one of the best acted comedies that we have seen for years.1

The reviewer from the Era – who this time I can say with a good deal of assurance probably was E.L. Blanchard -- said of the play:

We have to congratulate Mr. Webster upon having produced at his theatre decidedly the best piece which has been brought out in London for many a day. It may not contain a wonderfully clever plot—it may not in its construction display a great amount of highest talent—it may not possess unrivalled dialogue, and be altogether the most original thing of its kind we have seen of late; but it is, to our thinking, what we have just declared it to be, for it is precisely what was wanted, and it is calculated to do a great deal of good, while it affords a vast amount of amusement. It has many merits. In the first place, it breaks what may almost be termed new ground —so long is it since John Bull has had the vices or, if you like, the follies of his “saints” boldly exhibited and irresistibly ridiculed. It is a fair retaliation and one hard, solitary, right-handed blow in return for all the attacks that have been made upon the stage for years past —and it tells. The audience subscribes to the justice of the castigation, and their approval is manifested not only in roars of laughter, but that hearty chuckle which is less empty and less questionable for we may laugh at what we cannot approve.2

The following critic described the ebullient mood of crowd at the play’s ending:

The house was crowded, and the laughter and applause were incessant. We never witnessed a heartier welcome to any dramatic novelty. At the fall of the curtain the call for the performers was unanimous and irresistible. The curtain rose on the whole group, from which Mr. Webster advanced towards the audience, and, amidst tumultuous applause, announced the repetition of the piece on every night not appropriated to Mr. Macready’s performances.

This was followed by a vociferous call for the author. It was loud, long, and not to be denied – at last Mr. Morris Barnett bowed his acknowledgments from a private box, and the popular entertainments of the evening proceeded.3

Today, seeing an author take a bow at the premiere of a play may be an empty and hackneyed Broadway convention. In 1849, the honor was still a relative novelty bestowed on few dramatists. Barnett might have been taken particularly by surprise since “The Serious Family” was a work that was not only based on a translation of a French play, but a comedy that was itself indebted to a another more well-known theatre classic.

References in the reviews make it clear that many of these critics had seen Bayard’s “Le Mari à la Campagne” when the Comédie-Française had visited the St. James Theatre the year before. They were perfectly aware that the French play was the source of Barnett’s comedy. Most, like the following commentator, found “The Serious Family” to be the superior production;

In converting the French piece into an English one Mr. Barnett has displayed remarkable tact und talent. Laying his scene in London, he has given a new colouring to his characters, and has made several alterations in the grouping of his figures, by which he has greatly heightened the general effect. The grim family are endowed with attributes belonging to an English atmosphere, and the predilection shown by some of our philanthropists for remote miseries, while those of our own metropolis are overlooked, is felicitously satirized.4

Several reviewers seemed aware that Bayard and Barnett had a common source in Moliere. A few actually preferred the Victorian era revisions to Tartuffe. Several of these writers appreciated the comedy value of the up-to-date topical humor that Barnett had added. One critic specified that they felt that Moliere had erred by using bawdy humor to excoriate bawdy behavior;

The author has ventured upon delicate ground. The vice which he censures, though common and mischievous, wears yet a mask to closely resembling a sacred virtue that many generous and even enlightened minds are its unconscious victims. The Tartuffe of Molière, and its English version, The Hypocrite, have already recommended to public execration the heartless wickedness which does not hesitate to assume the fair garb of religious enthusiasm, that it may the more easily accomplish its designs against the innocence or the wealth of those whom it would betray.

These works, though justly severe, are coarse in their satire, and the line between the excellence which they would uphold and the depravity which they would condemn is so imperfectly marked that not a few are misled as to the real purpose of the writers. The Serious Family is not chargeable with an error so grave. In every line of this comedy the discrimination between real and affected piety is perfectly sustained, and the great lesson intended to be enforced is so clearly read that the veriest child receives it in the fullness of its meaning and the reality of its purpose. 5

Barnett’s play, in this reviewer’s opinion, made an equally strong point in condemning religious hypocrisy without offending the delicate sensibilities of its viewers as by indulging in an excess of carnality to do so.

Although not as robust a critique of hypocrisy as Moliere’s original, with its strengthened romantic subplots, updated topical references, and tightened focus on the stifling influence of the condemning puritanical matriarch, Barnett’s comedy was, as the Era’s critic (probably E.L. Blanchard) proclaimed,

The Serious Family is precisely what everybody ought to witness, for it not only amuses, but edifies, and is “a delicious dig” for the uncharitable charity-mongers of the day.6

Next week I examine some of the critical differences between Bayard and Barnett’s plays, looking in depth at a few of the characters unique to “The Serious Family” that might have made them particularly attractive to an audience of 1849 – including Anna Cora Mowatt – in the days when Polkamania raged.

Notes:

“Haymarket Theatre.” The Sun. Wednesday, Oct. 31, 1849. Page 6, col. 6.

“Haymarket – “The Serious Family.” The Era. November 4, 1849. Page 11, col. 1.

“Haymarket Theatre – The Serious Family.” The Morning Post. Wednesday, Oct. 31, 1849. Page 6, col. 3

“Haymarket Theatre.” Bell’s Life in London. November 4, 1849. Page 3, col. 1

“Haymarket Theatre – The Serious Family.” The Morning Post. Wednesday, Oct. 31, 1849. Page 6, col. 3

“Haymarket – “The Serious Family.” The Era. November 4, 1849. Page 11, col. 1.

Comments