Anna Cora Mowatt and a Pair of “Breeches”

- Jul 5, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2023

Originally published Nov. 30, 2020

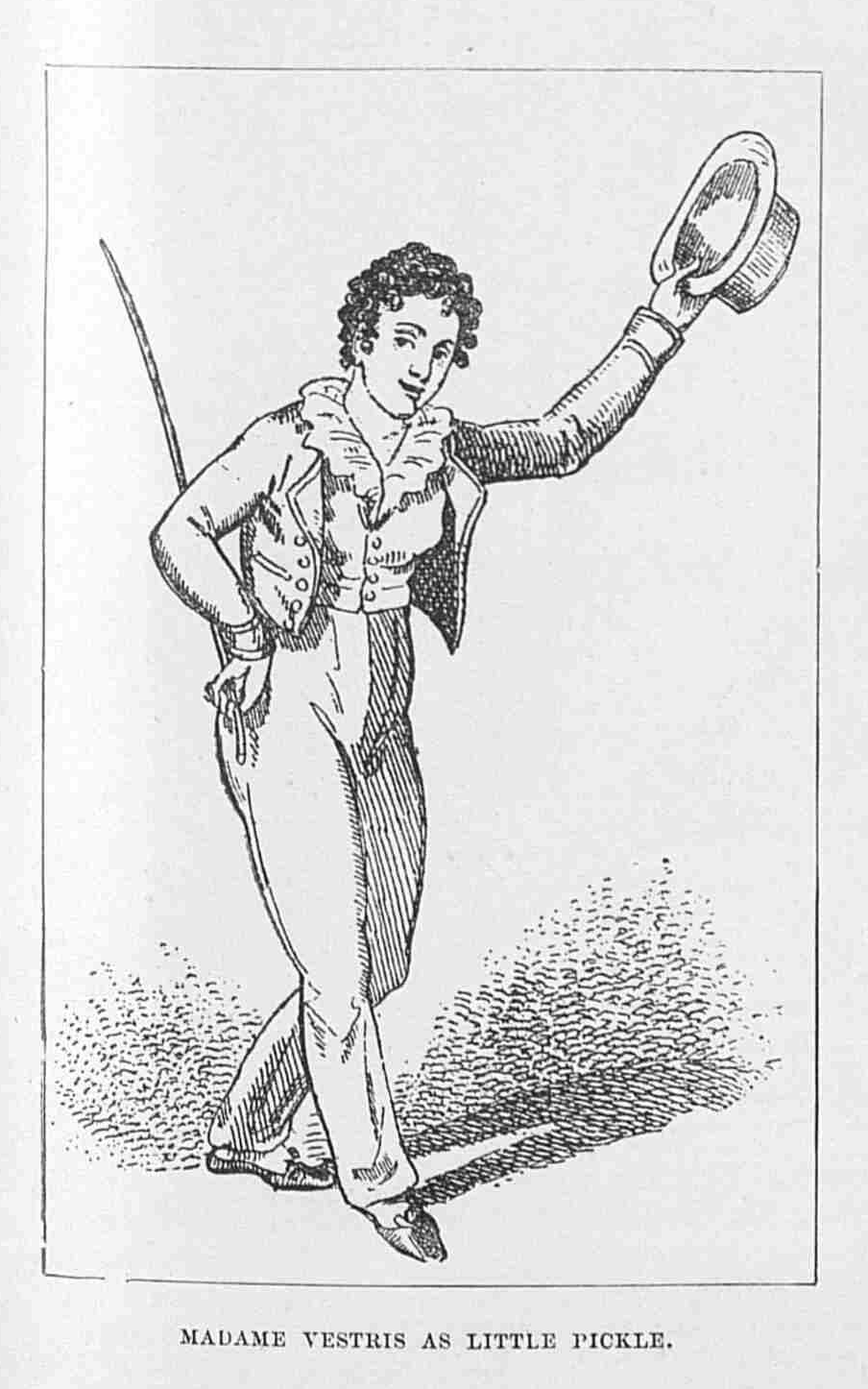

As a woman who simultaneously achieved international fame as both a playwright and an actress, Anna Cora Mowatt holds a unique position in early Victorian theatre history. As someone who knew the world of the playhouse from both backstage and front of house, she brought an impressive breadth of knowledge about theatrical practices and tastes to bear when composing her dramas. On the topic of the so-called “breeches roles” in which women played male characters, I think it is instructive, therefore, to look at her choice to include such parts in two of her plays. She was the only individual I know of from this era of who not only played characters in which she appeared in male garb (Rosalind in “As You Like It,” and Talford’s “Ion”) but also wrote roles in which women played male characters (Amurath in “Gulzara” and Victor in “Armand”).

Mowatt’s first play, “Gulzara,” was created to be performed by herself and her sisters at her father’s opulent home in Ravenswood, N.Y. The limited size and personal preferences of her cast put certain restrictions on her composition. As she states in her autobiography;

The play was rapidly completed; but I had had some formidable difficulties to overcome in its construction. We objected to admit gentlemen into our corps dramatique, — to say the least, their presence was an inconvenience, — yet our youthful company wished to avoid assuming male attire. I must write them a play without heroes. To suit these caprices I invented a plot, the scene of which was laid within the walls of a harem.1

Although Mowatt met with resistance from her cast to the idea of performing a role that would call for wearing male garb, in the end, she did create one part that would call for a female performer to play a male character. “Gulzara,” a full-length, five act drama, has a tiny cast of only five characters. Sultan Suleiman, who serves as the romantic male lead for the plotline, is frequently mentioned by the other characters, but never makes an onstage appearance. His daughter, Zuleika, takes on the function of the central authority figure in the drama. In his absence, she takes on the responsibilities of ruler and head of the family. She is assisted by Fatima, one of the absent sultan’s wives, who serves as her advisor and sounding board, and Katinka, a servant. Gulzara is the female romantic lead of the piece. As the title indicates, the play is essentially her story. Ayesha, a fisherman’s wife who has been wronged by Suleiman, serves as the play’s antagonist. Rounding out the cast is Amurath, Suleiman’s favorite son, a quick-witted and lively little boy.

Mowatt wrote the role of Amurath for her young sister, Julia. She considered her little sister a very talented performer and wrote the part to showcase the girl’s ability to effectively play both drama and comedy. Mowatt describes the part;

The only male character is that of the sultan’s son Amurath, a boy ten years old. This character was written for little Julia, and I expended all the ability I possessed in making the part one that would afford ample scope for the display of her brilliant talents. It was a part in which she could fairly compete with Gulzara, (which I enacted,) and, as the sequel proved, could bear away the palm.2

Structurally, Amurath, though a male character, serves the function of melodrama’s archetypical “damsel in distress” in the plotline. He is courageous and plucky, but has few real responsibilities. This energetic little boy is admired and pampered by all the other characters. Amurath is imperiled by Ayesha, the antagonist. This action, in turn, endangers Gulzara, the romantic lead. Both Amurath and Gulzara demonstrate agency in extracting themselves from hazard. There is no powerful adult male character to rescue them. Amurath takes physical action. Gulzara makes a moral stand and uses the power of rhetoric to resolve the threat she faces.

Although three of Mowatt’s sisters expressed reservations about appearing on stage in male garb, little Julia must not have objected. It is possible that, given the creative ingenuity she demonstrated in crafting the drama, Mowatt could have come up with a female character for her sister to play who would have served the same plot function as Amurath. Selecting the sultan’s heir as a character in who is placed in great danger considerably ups the stakes in the dramatic situation she creates. However, if playing a boy’s role had been deemed totally unacceptable, it is not difficult to envision Mowatt substituting an appealing daughter to serve as an object of anxiety in the plot. Since Amurath is a child, he has no love scenes to play. Although he is lavished with affection by the other characters, the performer of this character is not responsible for creating any sense of sexual tension with anyone else. Neither is the actress called on to present a convincing appearance of stereotypical masculinity as defined by the era. Amurath has more emotional flexibility than one associates with adult male characters in melodramas. He can quickly switch from being vain and boastful to being frightened and vulnerable without seeming inconsistent or inappropriately weak. Amurath does act bravely, but has to give himself pep talks to make such boldness possible as in this scene;

No help then? no escape? here must I die!

It may be – but not like the foolish hare

In fear expiring – with no struggle made

For liberty –no effort — or to dry

The flood that for me now is swelling, or

To give it better cause to rise. [sits down.] I’ve heard

My father say what cities’ strength has failed

To conquer, stratagem must win; I’ll think

Amurath’s exuberance and inflated sense of self-esteem provide the few moments of comic relief in “Gulzara.” By crafting this breeches role as a humorous one, Mowatt guides the audience from the boy’s first appearance not to take the character too seriously. Amurath, thus becomes a character listeners are invited to laugh with, not laugh at.

[Listen to an audio recording of this play here]

Mowatt also deftly incorporated comedy in the writing of her second breeches part when she created the role of Victor in “Armand.” This play was written two years after the debut of her hit comedy, “Fashion,” at the request of Mr. Simpson, the manager of the Park Theater in New York. Simpson was so anxious for a follow-up to “Fashion” and so assured of its potential success that he set dates for the premier of this show before Mowatt had started writing a line of dialogue. In contrast to “Fashion” which she wrote having seen very few plays on stage let alone act in one, Mowatt had been touring the East Coast for two years as a star player when she composed “Armand.” Acting the part of Gertrude in multiple productions of “Fashion” had shown her the flaws and limitations of that script from an actor’s point of view. Mowatt designed “Armand” from the ground up to be not just appealing to audiences, but to better meet the needs and preferences of the performers who would enact the script. I think it is significant, then, that one of her choices was to include a comic breeches part in the script in the form of Victor, the self-important page to Louis XV.

Melodrama seems to us today to be… well, very melodramatic. This form is characterized by exaggerated emotions and sensational plot twists. Mowatt, as was not entirely uncommon, deployed the technique of including humorous minor characters to keep her drama from getting too heavy-handed. In addition to lightening the overall mood, these characters were also responsible for delivering vital expository information that kept the action moving along at a sprightly pace.

As playwright turned performer, Mowatt had to endure the torture of listening to fellow players murder her dialogue nightly in productions of “Fashion.” A good portion of the wit in that show is epigrammatic, depending on skillful delivery of the precise wording from the script for the humor to work. After enduring countless episodes of hearing actors kill jokes by forgetting lines or substituting clumsy improvisations, Mowatt went with a much simpler approach to comedy in “Armand.” Like the writer of a classic sitcom, she gave each of these eccentric minor characters a single, simple comic hook. Dame Babette is a babbling gossip who continually protests variations on her catchphrase, “Oh! I say nothing – I never talk!” Le Sage is an unctuous courtier who speaks primarily in adverbs. Victor is pompous servant with delusions of grandeur who habitually uses the royal “we” to refer to himself… and has great difficulty in remembering not to do so when speaking to the king.

As she did with Amurath in “Gulzara,” Mowatt lightens the load of the actress playing the breeches role by making the part comic. It does not matter if the performer is unable to completely trick the audience into believing that she is a man. The character as written is meant to be a bit ridiculous. Moments when audience can see through the actress’ masquerade and maintain a double awareness that this character is actually a female performer in male disguise only adds to the fun of the viewing experience. Victor is a character who wishes to be something he isn’t – a king – played by an actress pretending to be something she’s not – a man. From the first moment on stage, other characters begin to comment on Victor’s appearance as in this exchange with Le Sage:

Victor. Ah! Monsieur Le Sage, we are charmed to encounter you. Le Sage. Delightedly I salute his Majesty in miniature. Victor. If you reflect on our size, Monsieur Le Sage, we would inform you — Le Sage. That it is immeasurably beneath my notice. — A particularly correct and pungently philosophical conclusion.4

Rather than trying to conceal the gender-swap, dialogue like this serves to invite the audience in on the joke, inviting viewers to spot and relish the flaws in the mimicry taking place. Victor, in imitation of the lustful Louis XV, attempts to present himself as a great lover of women as in the following;

Victor, Ah ! you touch us nearly when you talk of her! Our love for the “illusive sex” — for such we deem them — is our Achilles’ heel — our vulnerable point! His Majesty, like ourself, has been cold for a season; but once more the intoxicating effect of the tender passion has overpowered.5

To draw even more attention to the masquerade taking place, Victor is a lady/man who is trying to pass himself off as a ladies’ man. How little the other characters are convinced by his charade is revealed in the following exchange;

Vic. Monsieur Le Sage! Our dear Monsieur Le Sage! We are overwhelmed by the sight of his Majesty’s affliction. One moment he is like an angry child disappointed of its plaything, the next a very woman deluged in tears. But we can sympathize with him; we know the pangs which a passion for th’ illusive sex too surely inflicts. We have suffered ourselves. Le Sage. Possibly.6

Mowatt employs wordplay in these two passages that an auditor might not have been able to distinguish when she has Victor term women the “illusive” sex instead of the “elusive.” Mowatt is creating an exquisite moment of meta-commentary here. The actress speaking these lines is herself engaged in trying to create the illusion that she is a young man, thus serving as a demonstration of the “illusive” skills and propensities of women. With this malaprop-like selection of term that on the surface seems to be the wrong word, but on a deeper level speaks the truth about the performative circumstance created, the performer playing Victor is not trying to elude or run away from the theatricality of their situation, but rather inviting the audience to maintain a pleasurable double awareness of the illusion she is creating/not creating.

[Listen to "Armand" here]

Although most Theatre historians will quickly point out (as I have done several times over the course of the last three blog entries…) that a primary purpose of breeches roles on the Victorian stage was usually to enhance the sex appeal of productions by providing opportunities for audiences to look at lovely ladies’ legs, these two examples from the work of Anna Cora Mowatt demonstrate that this choice could serve other artistic functions as well. Just as with the so-called “pants parts” in opera still in use today, playwrights sometimes chose to have high-spirited young men and boys played by young women to achieve certain effects. Because of prevalent notions about gender and the display of emotion, a writer might feel that a female performer would have greater range and flexibility when conveying the exuberance and energy of such a character. Also, as Mowatt may have intended with Amurath in “Gulzara,” a playwright might wish to heighten the audience’s sympathy for an endangered character by having him portrayed by an actress, who, again, their cultural biases would mark as being more vulnerable. Finally, just as Mowatt does when she has “Armand’s” Victor speak of the “illusive sex,” breeches roles can be deployed to create playful meta-commentary on the artificiality of the genre itself.

Either way, Mowatt’s young men played by young women were more than just a pretty pair of legs.

Mowatt, Anna Cora. Autobiography of an Actress; or Eight Years on the Stage. (Ticknor, Reed, and Fields: Boston, 1856) Page 132.

Ibid, page 133.

Mowatt, Anna Cora. “Gulzara; or the Persian Slave.” The New World, Quarto Edition, v. II, no. 17, Whole Number 47, Saturday, April 24, 1841. Page 262.

Mowatt, Anna Cora. Armand; or the Peer and the Peasant. Stinger and Townsend: New York, 1851. Page 10.

Ibid. Page 11.

Ibid. Page 28.

Comments